Loyola Law Magazine 2024 - Digging deep

“There’s very little focus on clemency for folks who have been rehabilitated,” Woods says. “We’re constantly thinking about how to do our work in a way that is replicable.”

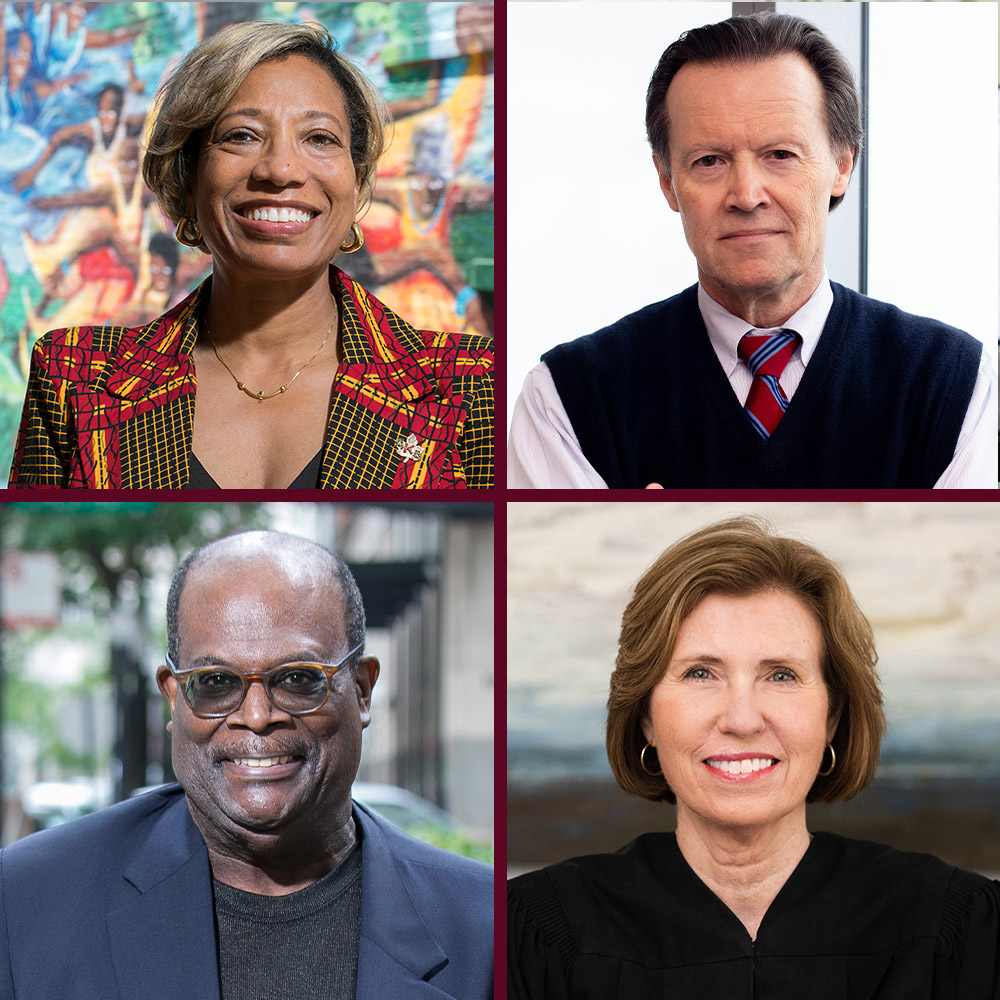

Loyola Law Magazine 2024 Profile Nadia Woods (JD ’21)

Digging deep

Nadia Woods (JD ’21) works to release rehabilitated and terminally ill people from prison

As a staff attorney at the Illinois Prison Project, Nadia Woods (JD ’21) strives to secure release for people serving long prison sentences who have experienced rehabilitation or are medically incapacitated. She is also an adjunct professor at the School of Law, where she works to inspire students to follow her lead.

What drew you to social and criminal justice work?

With Southern roots, I was cognizant at a very early age of how folks are systematically treated differently. Then in my teenage years, I got involved with organizing, especially around reproductive justice. That’s how I began to understand how social justice and bottom-up organizing are all about helping folks live in a way that they’re supported by their society, not oppressed by it.

Tell us about your work with the Illinois Prison Project.

IPP is focused on decarceration in Illinois, and clemency is the bread and butter of our work. We believe [society] should embrace the value of rehabilitation in the criminal legal system. If folks have been in prison for decades—even if they are guilty of the crime they were convicted of—they should be granted mercy so they can rejoin society and contribute in a way that benefits themselves and others.

Most of the work I do at IPP right now is on medical release cases. These folks are terminally ill, expected to live less than 18 months, or they are medically incapacitated and rely on corrections staff to support them every day with activities like using the bathroom or eating. We help give them the opportunity to die surrounded by their loved ones instead of by prison staff.

I personally have supported five folks through that mechanism, and IPP as a whole has helped get more than three dozen folks home. Still, there are dozens and dozens more incarcerated people eligible for medical release, but there are not dozens and dozens of attorneys lining up to represent them.

“We spend months getting to know our clients, their families, their communities, to really understand their stories.” Nadia Woods (JD ’21)

What is the key to a successful clemency petition?

Before we file anything, we spend months getting to know our clients, their families, their communities, to really understand their stories [and] include the full context in the petition. Oftentimes our clients tell us this is the first time that their full, nuanced story has been told. We can do that because clemency cases are not as restricted as trial-level filings or criminal court filings. The work emphasizes our writing and storytelling skills.

How big is the problem of overincarceration?

The problem is way bigger than most folks could ever imagine, and yet it’s not acknowledged by society. Cases in which people were wrongfully convicted do get some attention, but there’s very little focus on clemency for folks who have been rehabilitated. Our small team at IPP can’t do all there is to do, so we’re constantly thinking about how to do our work in a way that is replicable—in a way that other folks can use what we’ve learned, through failure and through success, to advocate for others.

What’s a question you get frequently?

People often ask us how we can represent folks who maybe took someone’s life. My answer is always the same: I wish you could sit down with one of my clients [and] hear directly from them how remorseful they are, how they have changed, and what they’ve been doing during 30 years of incarceration to give back to other people.

The realities of incarceration are hidden from society, but if folks had some descriptive detail about what people deal with in prison, I believe more would support our work. I encourage people to listen to podcasts like Violation or Ear Hustle and read publications like Stateville Speaks; they all feature stories by and about incarcerated folks. They show that humanity ties us all together.

Did you know?

Nearly 30,000 people are imprisoned in Illinois, four times as many as in 1971.

Source: Illinois Prison Project

What criminal justice reforms are most urgently needed?

Station house representation is a big issue in Chicago. Once somebody has been arrested and taken to a police station, they are legally allowed to have an attorney there to advocate on their behalf, and they’re also allowed to assert that they will not answer any questions without an attorney present. As recently as five years ago, something like 5 percent of folks arrested in Cook County were receiving that attorney. The urgency is to educate people so that they know their rights and so that, 20 years later, they’re not still trying to prove their innocence after a coerced confession.

Another urgent issue has to do with parole. Because of the way parole laws are structured in Illinois, the vast majority of people in [Illinois Department of Corrections] custody who are eligible for parole are older men sentenced before 1978. Many have been denied parole dozens of times, in part because they don’t have representation, which isn’t required. But I think the other reason is that there isn’t enough monitoring of how parole decisions are made by the Prisoner Review Board. –The PRB is made up of laypeople who get paid to make huge decisions about other people’s lives. More than 95 percent of the cases that we handle at IPP are decided by the PRB, and we see some disturbing patterns from certain board members—like some who tend to vote “no” regardless of the incarcerated person’s growth or situation. Going up in front of the board can feel like going up in front of the politics of those specific members. It shouldn’t be political; they should be doing right by these folks and acknowledging rehabilitation where it exists.

What can attorneys practicing in other areas of the law do to support your work?

IPP has cohorts of pro bono attorneys, so anyone interested in learning how to represent folks in the clemency process should reach out to IPP. We have one cohort specifically focused on survivors of domestic violence who are incarcerated as a result of how they survived. Attorneys can also volunteer to represent folks at police stations through organizations like the National Lawyers Guild. Maybe the easiest way they can get involved is to invite us to their office or organization so we can talk about clemency and the importance of humanizing your clients. –Liz Miller (July 2024)

Faculty research

Some recent and forthcoming School of Law faculty publications related to criminal justice

Blanche Cook, Something Rots in Law Enforcement and It’s the Search Warrant: The Breonna Taylor Case, 102 Boston University Law Review 1 (2022)

Adam Crepelle, Military Societies: Self-Governance and Criminal Justice in Indian Country, Public Choice (2022) (with Tate Fegley and Ilia Murtazashvili)

Adam Crepelle, Making Red Lives Matter: Public Choice Theory and Indian Country Crime, 27 Lewis & Clark Law Review 769 (2023)

Maria Hawilo, ed., Dismantling Mass Incarceration: A Handbook for Change (Macmillan, 2024) (with Premal Dharia and James Forman Jr., eds.)

Maria Hawilo, Past, Prologue, and Constitutional Limits on Criminal Penalties, 114 The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 51 (2024) (with Laura Nirider)

Stephen Rushin, The Effect of Police Quota Laws, 109 Iowa Law Review __ (forthcoming 2024) (with Griffin Edwards)

Dean Strang, Inaccuracy and the Involuntary Confession: Understanding Rogers v. Richmond Rightly, 110 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 69 (2020)

What drew you to social and criminal justice work?

With Southern roots, I was cognizant at a very early age of how folks are systematically treated differently. Then in my teenage years, I got involved with organizing, especially around reproductive justice. That’s how I began to understand how social justice and bottom-up organizing are all about helping folks live in a way that they’re supported by their society, not oppressed by it.

Tell us about your work with the Illinois Prison Project.

IPP is focused on decarceration in Illinois, and clemency is the bread and butter of our work. We believe [society] should embrace the value of rehabilitation in the criminal legal system. If folks have been in prison for decades—even if they are guilty of the crime they were convicted of—they should be granted mercy so they can rejoin society and contribute in a way that benefits themselves and others.

Most of the work I do at IPP right now is on medical release cases. These folks are terminally ill, expected to live less than 18 months, or they are medically incapacitated and rely on corrections staff to support them every day with activities like using the bathroom or eating. We help give them the opportunity to die surrounded by their loved ones instead of by prison staff.

I personally have supported five folks through that mechanism, and IPP as a whole has helped get more than three dozen folks home. Still, there are dozens and dozens more incarcerated people eligible for medical release, but there are not dozens and dozens of attorneys lining up to represent them.

What is the key to a successful clemency petition?

Before we file anything, we spend months getting to know our clients, their families, their communities, to really understand their stories [and] include the full context in the petition. Oftentimes our clients tell us this is the first time that their full, nuanced story has been told. We can do that because clemency cases are not as restricted as trial-level filings or criminal court filings. The work emphasizes our writing and storytelling skills.

How big is the problem of overincarceration?

The problem is way bigger than most folks could ever imagine, and yet it’s not acknowledged by society. Cases in which people were wrongfully convicted do get some attention, but there’s very little focus on clemency for folks who have been rehabilitated. Our small team at IPP can’t do all there is to do, so we’re constantly thinking about how to do our work in a way that is replicable—in a way that other folks can use what we’ve learned, through failure and through success, to advocate for others.

What’s a question you get frequently?

People often ask us how we can represent folks who maybe took someone’s life. My answer is always the same: I wish you could sit down with one of my clients [and] hear directly from them how remorseful they are, how they have changed, and what they’ve been doing during 30 years of incarceration to give back to other people.

The realities of incarceration are hidden from society, but if folks had some descriptive detail about what people deal with in prison, I believe more would support our work. I encourage people to listen to podcasts like Violation or Ear Hustle and read publications like Stateville Speaks; they all feature stories by and about incarcerated folks. They show that humanity ties us all together.

What criminal justice reforms are most urgently needed?

Station house representation is a big issue in Chicago. Once somebody has been arrested and taken to a police station, they are legally allowed to have an attorney there to advocate on their behalf, and they’re also allowed to assert that they will not answer any questions without an attorney present. As recently as five years ago, something like 5 percent of folks arrested in Cook County were receiving that attorney. The urgency is to educate people so that they know their rights and so that, 20 years later, they’re not still trying to prove their innocence after a coerced confession.

Another urgent issue has to do with parole. Because of the way parole laws are structured in Illinois, the vast majority of people in [Illinois Department of Corrections] custody who are eligible for parole are older men sentenced before 1978. Many have been denied parole dozens of times, in part because they don’t have representation, which isn’t required. But I think the other reason is that there isn’t enough monitoring of how parole decisions are made by the Prisoner Review Board. –The PRB is made up of laypeople who get paid to make huge decisions about other people’s lives. More than 95 percent of the cases that we handle at IPP are decided by the PRB, and we see some disturbing patterns from certain board members—like some who tend to vote “no” regardless of the incarcerated person’s growth or situation. Going up in front of the board can feel like going up in front of the politics of those specific members. It shouldn’t be political; they should be doing right by these folks and acknowledging rehabilitation where it exists.

What can attorneys practicing in other areas of the law do to support your work?

IPP has cohorts of pro bono attorneys, so anyone interested in learning how to represent folks in the clemency process should reach out to IPP. We have one cohort specifically focused on survivors of domestic violence who are incarcerated as a result of how they survived. Attorneys can also volunteer to represent folks at police stations through organizations like the National Lawyers Guild. Maybe the easiest way they can get involved is to invite us to their office or organization so we can talk about clemency and the importance of humanizing your clients. –Liz Miller (July 2024)