archive

New Digital Site Explores British Reaction to Call for American Independence

.jpg)

Kate Johnson, Marie Pellissier, and Kelly Schmidt created Explore Common Sense to discover how the British reacted to Tom Paine's call for American Independence.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense inspired American colonists toward revolution, but what did the British think of his words?

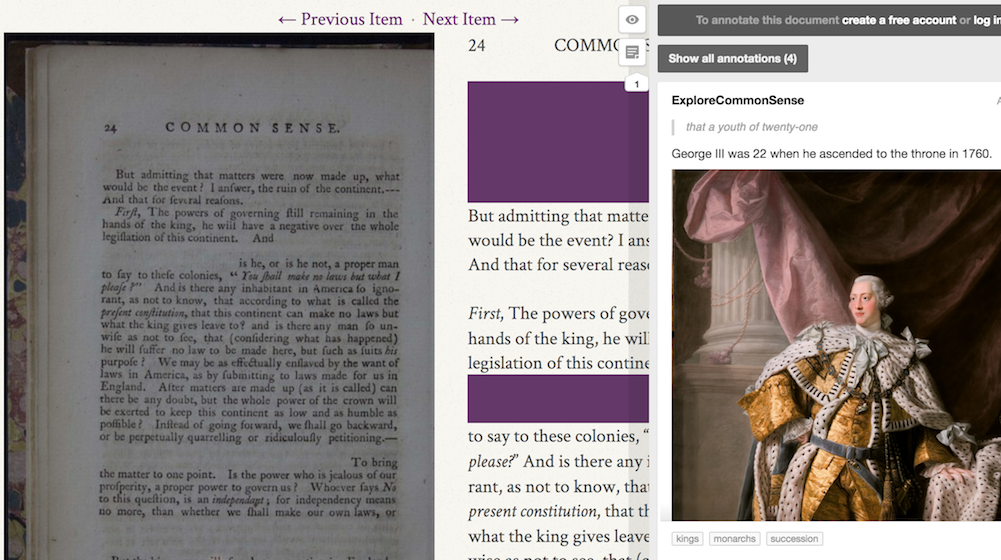

Kate Johnson, Marie Pellissier, and Kelly Schmidt, graduate students at Loyola University Chicago, set out to find an answer to this question this past spring. The answer surprised them and inspired them to create a digital critical edition of Common Sense that explores a re-printing of Thomas Paine’s iconic pamphlet produced by printer J. Almon in London in 1776. Unlike American editions, Almon censored portions of the text in this British version by simply leaving blank spaces in the typesetting where the objectionable words had been. Historians have spent much time studying the impact of Common Sense on the American consciousness in the days leading up to revolution. However, the thoughts and reactions of British readers have received less attention. Explore Common Sense (explorecommonsense.org) offers insights into what readers across the pond thought of this provocative tract.

We recently caught up with Kate, Marie, and Kelly and asked them some questions about the project:

There are a range of iconic publications from the period of the American Revolution. Why did you choose Common Sense to create a digital edition around?

Kate: The simple answer is because that is the document we had access to. We were fortunate in that Loyola University Archives and Special Collections had recently acquired a copy of the first British edition of the iconic pamphlet, and when we had the chance to work with scans of the document in an American Revolution class with Dr. Kyle Roberts, we knew we had a fantastic opportunity on our hands. While Common Sense has been established as being a very influential piece in the patriot movement in America, analyzing the British edition gives us a chance to explore its influence from a different perspective.

Common Sense was published almost 250 years ago. What does it have to say to us today?

Kate: A lot! Both in terms of what it can tell us about people and events in the past, but also in ideas and concepts that we can continue to ponder and grapple with today. Political discontent and the power of words in shaping public opinion are as relevant today as they were in 1776. The Revolutionary period in American history continues to be an important source for shaping our national identity, and this British edition in particular gives us an opportunity to better appreciate how both American Colonists and British subjects perceived and understood the striking political changes that were unfolding around them. There is much that we can still learn from this document, and Explore Common Sense provides an avenue for us to engage with the text as it was grappled with by its first readers: through dialogue with each other about its message and meaning.

What can we learn about Common Sense from a digital site that we can't by just looking at a physical copy?

Kelly: Exploring Common Sense digitally opens several opportunities to view the text in a new light. What prompted our decision to make a digital critical edition in the first place was the uniqueness of the version we had available to us--the first British edition. The London printer, J. Almon, concerned about being charged for seditious libel for publishing Paine's pamphlet, removed portions of the text that might get him in trouble with the Crown, but left glaring gaps where those phrases used to be. To someone looking at the physical copy without reference to the American edition, it is not necessarily evident what Almon removed and why. Creating a digital edition allowed us to highlight the redacted portions of the text so that when a user hovers a mouse over the highlighted portion, the missing words appear. Annotations that appear when a user clicks on the text provide further contextualization about why these lines were removed. Additionally, for scholars wishing to analyze the text more closely, tags and search functions enables visitors to the site to measure the frequency with which certain topics or themes within the text come up.

Was this your first collaborative digital project? What was it like as historians to work together on a project instead of individually?

Marie: Working on digital projects, I've learned that it's almost impossible to do digital humanities work completely solo. As an undergrad, I worked on a "solo" project, but even that wasn't completely by myself--I was using a platform created by the media services department at my university and constantly consulting with the developers of that platform, since I didn't have any coding skills.

Working on Explore Common Sense has been a fantastic experience because each of us brings different strengths to the table. We're all learning from each other, and each of us has made invaluable contributions to the site. We've also had to make sure that we're really clear about project goals and expectations, so that we're all on the same page with what's happening. I think that collaboration like this is one of the most fun things about digital humanities projects! As historians, it's easy sometimes to get caught up in individual projects or to disappear into the archives, but digital projects like this one bring us together to work towards an end product that we hope will reach beyond the pages of a journal, into classrooms in universities and high schools.

What advice would you give to someone thinking about creating their own digital project?

Marie: Two things: First, have a solid sense of what you want your project to do, or the purpose you want it to serve. This is really important when it comes to developing the nuts and bolts of your project, and not letting yourself get sidetracked by all the cool bells and whistles! It's ok to have big, grand goals, but prioritize them, and make sure you have your first priorities done before you worry about anything extra.

Secondly, find a team! Ask around for people who are interested in the same thing who might want to jump on board. Look for people who have skills that you don't, or who will be able to contribute a unique perspective on your material. And, don't be afraid to ask people who aren't necessarily in the same location as you--a lot can be accomplished via email and teleconference! I've learned so much from the people I've collaborated with, and that collaboration has been one of the most valuable things I've taken away from this project.

Kelly: People often opt for a digital public history project over a more physical version because it allows for more widespread accessibility and (sometimes) less cost. However, digital projects have a tendency to "live with you" longer than, for instance, a physical exhibit or edited volume might. Because the internet is constantly evolving, the site requires ongoing monitoring and maintenance long after the development of the project has come to a close. Additionally, what might be saved in supply costs is made up for in the amount of time needed to develop, implement, troubleshoot, monitor, and provide upkeep for the project long term. This is especially the case in a site that is not static in that it encourages user contributions or has intentions to be an evolving, growing site, such as ours. Project team members need to be dedicated to monitoring and responding to user contributions, as well as adding new material to the site. Before considering initiating such a project, consider: do I have the time and technical skills to devote to this? Or do I have the resources to invest in using a more advanced program or developer? Is there an advantage to be gained in the project's digital format, or will it work well in another form?

You can explore the digital British edition of Common Sense at explorecommonsense.org.