archive

Celebrating Chrysler Village

Chrysler Village, the subject of an ongoing public history project by Loyola graduate students, is a neighborhood unlike any other in Chicago. Boarding Midway Airport on the southwest side of the city, Chrysler Village was established in 1942 to house 30,000 laborers who worked at the Chrysler-Dodge plant assembling B-29 “Superfortress” bomber engines during World War II. In addition to its role in wartime production, Chrysler Village is historically significant for foreshadowing national trends in postwar housing development. Its 700 housing units are similar to those seen in later planned communities like Levittown in their low-cost construction, uniformity of design, and financial dependence on the Federal Housing Act. Lastly, the layout of Chrysler Village is unique in Chicago because it does not conform to the grid system that defines the rest of the city's built environment. In “the village,” apartments, duplexes, and single-family homes are arranged concentrically along curving streets that surround Lawler Park at its center.

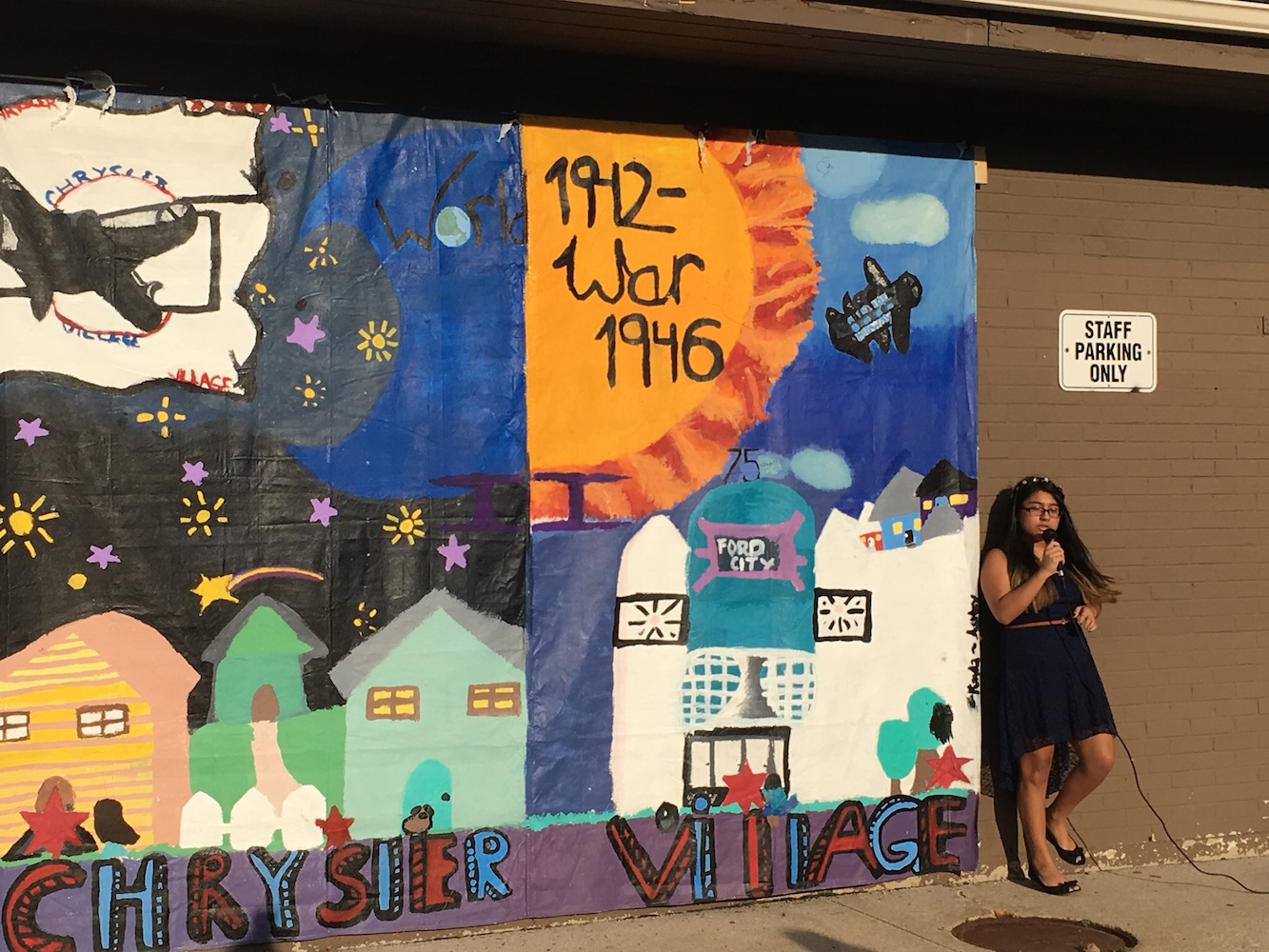

On a Tuesday evening this past August, Lawler Park was the site of the first ever Chrysler Village Community Fest. This was a collaborative event organized between students in Loyola's Public History Program, the Clear-Ridge Historical Society, the Office of Alderman Marty Quinn, the Chicago Park District at Lawler Park, local community members, teachers, and students from area schools. The festival brought together community members past and present to enjoy good company, free hotdogs, and a celebration of the area's rich past. The event showcased a community mural designed and painted by local students, an oral history booth for sharing memories, and a pop-up museum for neighborhood mementos. Lastly, commemorative signs were unveiled in honor of Chrysler Village's designation as a historic district.

Chrysler Village Community Fest is the most recent accomplishment of The Chrysler Village History Project, which was spearheaded by a group of Public History students in 2013 when they successfully nominated the neighborhood as a historic district to National Register of Historic Places. Over the last three years, Public History students have created a multifaceted, collaborative public history project through Loyola's student-driven Public History Lab with the goals of preserving and sharing the diverse histories of the Chrysler Village neighborhood.

* * *

On October 13-16th, Loyola University Chicago will host the Urban History Association's eighth biennial conference that will feature over 650 urban historians and scholars from around the world. As the History Department prepares for this exciting event, PhD Student Ruby Oram spoke with PhD Candidates Rachel Boyle and Chelsea Denault and PhD Student Kelly Schmidt about how they've put urban history into action through the collaborative Chrysler Village History Project.

* * *

How did this project start?

Chelsea Denault: We first became involved in this project during Dr. Karamanski's Management of Historic Resources graduate course in Spring 2013. The community's alderman, Marty Quinn, had approached Dr. Karamanski about nominating Chrysler Village to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) as a way to raise neighborhood pride and use that status as a way to advocate for city resources and services, which is a big deal in that neighborhood given its proximity to the noise, traffic, and pollution of Midway Airport.

Rachel Boyle: As part of our coursework, fellow Loyola history graduate students and I unearthed the neighborhood’s historical significance through extensive research in the archives and on the ground in Chrysler Village. Contributors to the NRHP nomination included: Joshua Arens, Courtney Baxter, Kim Connelly Hicks, Chelsea Denault, Mairead O’Malley, and Gregory Ruth. We continued to develop the nomination in the months after class until it was officially accepted in early 2014 and Chrysler Village was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

As satisfying as it was to help put Chrysler Village on the National Register, we couldn’t help but ask how the listing could better benefit the community. At the 2014 Annual Meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH), Kim Connelly Hicks and I joined a roundtable on preservation to discuss how we could build on our nomination to create a sustained, financially soluble, and socially relevant project for a changing community. The roundtable generated a host of great ideas, but as the original core of students moved on in their lives and careers, we needed leaders with a plan to move the project forward.

Once again, Chrysler Village entered the classroom. Dr. Mooney-Melvin offered to collaborate and integrate an assignment into her Public History: Methods and Theory course in fall 2015 that would introduce Chrysler Village to history graduate students and provide an opportunity to develop and present a public history proposal. Students pitched creative project plans that harnessed our National Register nomination research into dynamic public history projects for the benefit of the contemporary community of Chrysler Village.

Kelly Schmidt: I became involved in the Chrysler Village project through Dr. Mooney-Melvin's Public History Methods and Theory course. Rachel Boyle asked us as a part of the course to submit project proposals that would build upon the Chrysler Village nomination. The project sought ideas that would benefit the neighborhood socially and economically, and shed greater light on Chrysler Village's history and presence in the community, city-wide, and nationally. After the course concluded, Rachel invited those who were interested in reviewing these proposals and selecting components to put into action together to form a committee, and that's how the Chrysler Village History Project emerged. It has been an ongoing three-year effort across three different courses, an independent group of students, and invested members of the Chrysler Village community.

Rachel Boyle: Under the umbrella of Public History Lab, a handful of dedicated students decided to put their proposals into action after the course concluded. For example, Maggie McClain initiated a course collaboration with Dr. Manning to conduct oral histories of local residences. At the same time, Kelly Schmidt took the lead on bringing the idea of a community festival to the neighborhood. Over the course of a year, Kelly and fellow students periodically met with local residents and community leaders to refine the vision of the event and coordinate logistics.

Chelsea Denault: We decided our purpose was to preserve and celebrate the historical significance of the community, but we wanted to do so in a way that was accessible and engaging to everyone in the community. In the end, we pursued this mission in three ways. First, we began planning a Community Festival to raise awareness among the residents of the area's history while also building community. We also started an oral history project to collect and preserve the stories of residents. Finally, we created a website to document the project and also serve as an archive of articles, photos, oral histories, and other materials we've assembled over the the three years of this project.

Why have a Community Fest?

Kelly Schmidt: When Rachel Boyle's preservation cohort succeeded in nominating Chrysler Village to the National Register of Historic Places, neighborhood residents wondered, "So what? What does this nomination do for us?" Because residents felt that they missed out on community-building events that used to take place in the past, and sought more internal and external investment into their community, we thought that a Community Fest would be an ideal rallying point to bring neighbors together, encourage them to share their memories of the neighborhood and preserve them for posterity, and to evaluate interest in hosting larger community-building opportunities in the future, such as a festival celebrating Chrysler Village's 75th anniversary and the creation of a neighborhood association.

Rachel Boyle: The purpose of a community fest was to draw together neighborhood residents, both past and present, to celebrate Chrysler Village's rich history and current vibrancy. It was also an opportunity to collaborate with local elementary students to research their neighborhood's past, gather additional oral histories of longtime residents, and share information on how the National Register listing impacted homeowners. One of the most exciting results of the community fest was the collection of contact information for residents interested in starting a Homeowners or Civic Association. As a direct result of coming together and asserting the community's historical and contemporary significance, residents empowered themselves to organize and advocate for the tangible needs of their community.

What do you think are the greatest successes of this project so far?

Chelsea Denault: The greatest success of this project, to me, was the Community Festival! There was an unbelievable turnout of current and past residents, and such a wonderful atmosphere of community. It was so fulfilling to this key part of the project come to fruition, bringing people together to share their enthusiasm for their neighborhood. That feeling was particularly evident in the 50 signatures we collected from residents who were interested in starting their own neighborhood association.

Kelly Schmidt: Through the project we've begun to collect information about the history of Chrysler Village from its past and present residents--knowledge that might be implicitly known by some members of the community, but not by all, especially new arrivals to the neighborhood. We've been able to collect this information and make it publicly available in one place, The Chrysler Village History Project Website, which houses audio and transcriptions of oral histories with the residents as well as photographs and collections of documents from past and present residents and the local historical society. By being able to gather this material, we've been able to accomplish several goals. We've also been better able to contextualize the history of the people of Chrysler Village, about whom we formerly knew very little. Students in Dr. Manning's Oral History class wrote papers placing Chrysler Village's history within the larger context of Chicago and its neighborhoods, as well as similar communities throughout the nation.

Second, by posting this material digitally on a single website, we've made this material accessible to the Chrysler Village community and the general public. Through publicity help from Rob Bitunjac of the Clear-Ridge historical society, Chrysler Village residents, and local newspapers, residents past and present began to take a look at the site. It became a tool and network for community members and former residents to reflect on and reminisce about their neighborhood, both on the site and within Facebook communities. I was impressed to see that long-term residents and former residents used the comments section on our event page leading up to the Community fest to reconnect about their memories. They lamented that some elements of the neighborhood had changed, but praised many of the robust community events that used to take place, such as a neighborhood haunted house in the Lawler Park Fieldhouse, and the famous softball team that played in Lawler Park. One person even wrote that he was flying into Chicago to be at the Community Fest and used the comment section to reach out to a former neighbor to see if she would be in attendance!

Students of one resident's fifth-grade class also conducted research on local history topics in the area, and constructed posters that were placed on display along with materials from the Clear-Ridge Historical Society during the festival. One student even used the information we had gathered and shared to create a community mural, depicting important elements of Chrysler Village, past and present, that she unveiled at the event. They helped us achieve our goal of elevating attention to, and appreciation for, the community's history. Guests at the festival enjoyed learning about the history of the community and expressed that they previously had not known much about the neighborhood's origins.

Finally, we've seen a lot of momentum grow from our oral history and Community Fest efforts. Members of the neighborhood who'd like to see their community come together more often and share their commitment to the neighborhood used the Fest as an opportunity to gauge interest in forming a homeowner's association.

Rachel Boyle: No public history project can succeed without community investment, and we were so lucky to collaborate with an enthusiastic core of neighborhood residents and local leaders. The folks we worked with have such a strong commitment to advocating for their community and it was an incredible opportunity to lend our professional skills to support their goals. That we could help get them to a point to successfully start their own sustainable organization stands out as a great success of the project.

Secondly, throughout the three-year span of this project, a large number of Loyola graduate history students gave their time and skills to the Chrysler Village History Project. Whether coordinating logistics behind the scenes, travelling the 2.5-hour round trip to Chrysler Village for a community meeting, or volunteering the day of the community fest, so many dedicated students made this project possible. It was gratifying to support and coordinate the work of such passionate and capable public historians over the past three years, and I am proud to be part of program with students so committed to practicing public history for the benefit of local communities.

What's next?

Chelsea Denault: I would love to see our community collaborators build off of the enthusiasm everyone felt at the community festival and move forward with their neighborhood association. That would be the ultimate success in this project in my mind: that we had the opportunity to take a National Register nomination from a simple (well, not so simple) document back into the community and work with residents to foster a sense of place is truly incredible and speaks to the impact that public history can have when there's hard-working and passionate people - professionals and collaborators - involved in a project.

We also just presented the project at the American Association for State and Local History annual meeting in Detroit at the beginning of the month. We received so much positive feedback from public history professionals and scholars, many of whom encouraged us to apply for next year's award.

Kelly Schmidt: I would like to see the community take what we initiated into its own hands and use the momentum we gained together to build community, meeting residents' needs and desires. I hope that the Community Fest committee's efforts to create a homeowners' association that will host neighborhood events and bring neighbors together grows in popularity, and that they will continue to foster community growth through even bigger neighborhood events like the Community Fest each year.

Rachel Boyle: Some history graduate students are still following up on oral histories and maintaining our website as a resource for Chrysler Village, but overall our role in the project is coming to an end. Kelly and I are headed to the The National Council on Public History (NCPH) Annual Meeting in April along with a community collaborator to join other public historians in reflecting on best practices for transitioning full leadership of projects into the hands of the community. In the meantime, I look forward to seeing how Chrysler Village residents move forward with their plans to organize and advocate for their neighborhood.

Chrysler Village Community Fest, August 18th, 2016