Why is Ignatian Pedagogy Valued in Jesuit Education?

Why is Ignatian Pedagogy Valued in Jesuit Education?

While topics and texts may change, the underlying values of IP are the same: to educate “the whole person, head and heart, intellect and feelings” resulting in “a person who exhibits precision of thought, eloquence of speech, moral excellence, and social responsibility” (Kovenbach). Cura personalis: mind body and spirit. In challenging students to reflect on their learning, Jesuit educators hope to move students to assess how their learning impacts them as individuals and how it defines the individual’s relationship to the world.

As Fr. Pedro Arrupe outlined in his 1973 address, Jesuit education needs to reeducate for justice so our students become agents for change. Arrupe’s call is not a mere reiteration of the Church’s tradition but the “resonance of an imperious call of the living God asking his Church and all men of good will to adopt certain attitudes and undertake certain types of action which will enable them effectively to come to the aid of mankind oppressed and in agony.” Such work includes respect for all people, not profiting from our position of privilege and working to dismantle unjust social structures (Arrupe).

Ignatian Pedagogy in the 21st. Century

What has changed however, is the society in which our students reside: a virtually-enhanced world where conversations and interactions are as frequently communicated over mobile devices as in person and where a glut of information is available 24/7 from almost any location. And while this constant connectivity can assist faculty in dissemination of content and aide student learning, it can also present barriers to personal interactions at the heart of Ignatian pedagogical goals.

Former Superior General Adolfo Nicolas asserts that the nature of social media has a numbing effect on our students that makes it easy to “slip in to the lazy superficiality of relativism or mere tolerance of others and their views, rather than engaging in the hard work of facing communities of dialogue in the search of truth and understanding.” This superficiality, Nicolas contents, limits the “fullness of [students] flourishing as human persons and limiting their responses to a world in need of healing intellectually, morally, and spiritually.”

As Jesuit educators of the 21st Century, we are challenged to piece together the Ignatian principles to instill in our students a “depth of thought and imagination” that encompasses engagement with the reality of the world and the human condition (Nicolas). We are further challenged to leverage the technological tools that both enhance and distract from learning and put them to positive uses in and outside the classroom.

The Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm

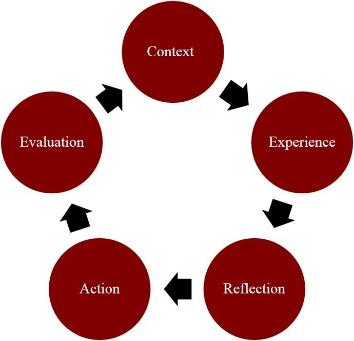

While education in the Jesuit tradition has generated from the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola and teachings of the early Society of Jesus educators, the Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm (IPP) is a relatively new depiction of Jesuit teaching values. Introduced in 1993, the paradigm as it is now typically illustrated was developed as a result of several years of study by the International Commission on Apostolate of Jesuit Education (Society of Jesus). To understand the relevance of the paradigm to Jesuit education, it is important to first define each of the five domains. While none of these ideas are unique to Jesuit thinking, application of the components of the IPP are distinctively Jesuit.

Ignatian Pedagogical Paradigm

The IPP can be applied to many different aspects of the educational process. We will consider here how faculty might use the questions inherent in the paradigm to think about their course design. It is important to remember, however, that the IPP is NOT a method of teaching but rather an overlay to course design that helps faculty ask questions about student involvement in the content and the meaning they ascribe to their learning.

Context: Who are our students and what can we expect them to bring to the course? Will they have a background in the subject matter, know how to use the requisite technology, have study skills or experience in research methods?

Experience: As faculty, we have all experienced the challenge of how one class can vary greatly from the next, even though the subject is the same. The answer to this difference may stem directly from context and looking at what our students bring with them to the course. What personal experiences do students have that we can draw on in designing course content? What types of content presentation will be most effective for their level of experience or background?

Reflection: The key to Ignatian reflection is that students add meaning and understanding to who they are becoming and what actions they will take as a result of what they are learning. What types of activities can be included in the course that will guide students toward analysis of the course concepts? What kind of guidance will be best for getting students to reflect on not just what they have learned, but what that content means to them, how it changes their view of themselves and the world, and how it calls them to action on what they have learned?

Action: Certainly the main objective of Jesuit education, action might be small changes the student makes in his or her behaviors or more global action that directs students toward becoming a “man or woman for [and with] others.” What types of activities can the professor include that will give students the opportunity to take their learning to meaningful action?

Evaluation: Much like the Examen in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, evaluation here challenges faculty to provide students with the opportunity to reflect on the process of action and what they have learned from their experience. In a well-structured evaluation exercise, students should then ask themselves what they did well and what they should do differently; but additionally, they need to evaluate WHY things worked or did not work as planned.

Teaching Practice:

Moving from the theory of Ignatian Pedagogy to teaching practice is something faculty may already be doing. Here are a few ideas to add to the lexicon of activities that may help students move into the meaningful learning practices that reflect Ignatian Pedagogy.

- Active Learning Strategies: have students stop and engage in the course material in a more meaningful and personal way. What examples can they find related to the content that are relevant to other classes, campus activities, current political situations, city or national news?

- Opinion Polls: periodically conduct anonymous polls to determine your students’ reactions to the materials. What is their understanding of the material or the concepts being taught? Are they able to apply what they are learning to another concept?

- Reflective Activities: Reflection does not have to come at the end of a course but can be used throughout to have students write about how they are interpreting what they are learning. What situation in their own life does this relate to? How is this content changing their views on how they view their surroundings? Their understanding of themselves?

- Student-Generated Content: have students bring in research, examples, ideas that relate to the course concepts. If a student brings something of particular relevance, share with the class and incorporate into the course materials. Having students bring in relevant content makes the course more their own and not just something dictated to them.

- Talk to students about why this subject matter is important in your discipline, to a general education or contributes to becoming a more informed person. What action have you taken as a scholar of your discipline? What actions do you continue to pursue to make you a person for others?

Works Cited

Arrupe, Pedro, S.J. “Men and Women for Others: Education for Social Justice and Social Action Today.” Address to the Tenth International Congress of Jesuit Alumni of Europe, Valencia, Spain. July 31, 1973.

Kolvenbach, Peter-Hans, S.J. As quoted in “Go Forth and Teach: The Characteristics of Jesuit Education.” Jesuit Secondary Education Association Foundations, 1986, pp. 18.

O’Malley, John W., S.J. “How the First Jesuits Became Involved in Education.” In The Jesuit Ratio Studiorum: 400th Anniversary Perspectives.” Vincent J. Duminuco, S.J., Editor. New York: Fordham University Press. 2000. Pp. 56-74.

Nicolas, Adolfo, S.J. “Depth, Universality, and Learned Ministry: Challenges to Jesuit Higher Education Today.” Remarks for “Networking Jesuit Higher Education: Shaping the Future for a Humane, Just, Sustainable Globe.” Mexico City, April 2010.

Society of Jesus. Ignatian Pedagogy: Practical Approach. 1993.

Why is Ignatian Pedagogy Valued in Jesuit Education?

While topics and texts may change, the underlying values of IP are the same: to educate “the whole person, head and heart, intellect and feelings” resulting in “a person who exhibits precision of thought, eloquence of speech, moral excellence, and social responsibility” (Kovenbach). Cura personalis: mind body and spirit. In challenging students to reflect on their learning, Jesuit educators hope to move students to assess how their learning impacts them as individuals and how it defines the individual’s relationship to the world.

As Fr. Pedro Arrupe outlined in his 1973 address, Jesuit education needs to reeducate for justice so our students become agents for change. Arrupe’s call is not a mere reiteration of the Church’s tradition but the “resonance of an imperious call of the living God asking his Church and all men of good will to adopt certain attitudes and undertake certain types of action which will enable them effectively to come to the aid of mankind oppressed and in agony.” Such work includes respect for all people, not profiting from our position of privilege and working to dismantle unjust social structures (Arrupe).

Ignatian Pedagogy in the 21st. Century

What has changed however, is the society in which our students reside: a virtually-enhanced world where conversations and interactions are as frequently communicated over mobile devices as in person and where a glut of information is available 24/7 from almost any location. And while this constant connectivity can assist faculty in dissemination of content and aide student learning, it can also present barriers to personal interactions at the heart of Ignatian pedagogical goals.

Former Superior General Adolfo Nicolas asserts that the nature of social media has a numbing effect on our students that makes it easy to “slip in to the lazy superficiality of relativism or mere tolerance of others and their views, rather than engaging in the hard work of facing communities of dialogue in the search of truth and understanding.” This superficiality, Nicolas contents, limits the “fullness of [students] flourishing as human persons and limiting their responses to a world in need of healing intellectually, morally, and spiritually.”

As Jesuit educators of the 21st Century, we are challenged to piece together the Ignatian principles to instill in our students a “depth of thought and imagination” that encompasses engagement with the reality of the world and the human condition (Nicolas). We are further challenged to leverage the technological tools that both enhance and distract from learning and put them to positive uses in and outside the classroom.

The Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm

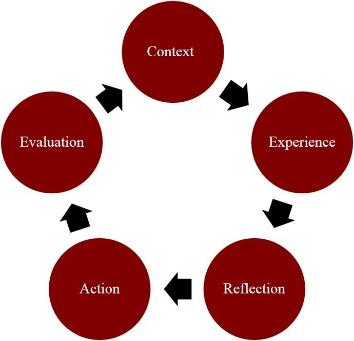

While education in the Jesuit tradition has generated from the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola and teachings of the early Society of Jesus educators, the Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm (IPP) is a relatively new depiction of Jesuit teaching values. Introduced in 1993, the paradigm as it is now typically illustrated was developed as a result of several years of study by the International Commission on Apostolate of Jesuit Education (Society of Jesus). To understand the relevance of the paradigm to Jesuit education, it is important to first define each of the five domains. While none of these ideas are unique to Jesuit thinking, application of the components of the IPP are distinctively Jesuit.

Ignatian Pedagogical Paradigm

The IPP can be applied to many different aspects of the educational process. We will consider here how faculty might use the questions inherent in the paradigm to think about their course design. It is important to remember, however, that the IPP is NOT a method of teaching but rather an overlay to course design that helps faculty ask questions about student involvement in the content and the meaning they ascribe to their learning.

Context: Who are our students and what can we expect them to bring to the course? Will they have a background in the subject matter, know how to use the requisite technology, have study skills or experience in research methods?

Experience: As faculty, we have all experienced the challenge of how one class can vary greatly from the next, even though the subject is the same. The answer to this difference may stem directly from context and looking at what our students bring with them to the course. What personal experiences do students have that we can draw on in designing course content? What types of content presentation will be most effective for their level of experience or background?

Reflection: The key to Ignatian reflection is that students add meaning and understanding to who they are becoming and what actions they will take as a result of what they are learning. What types of activities can be included in the course that will guide students toward analysis of the course concepts? What kind of guidance will be best for getting students to reflect on not just what they have learned, but what that content means to them, how it changes their view of themselves and the world, and how it calls them to action on what they have learned?

Action: Certainly the main objective of Jesuit education, action might be small changes the student makes in his or her behaviors or more global action that directs students toward becoming a “man or woman for [and with] others.” What types of activities can the professor include that will give students the opportunity to take their learning to meaningful action?

Evaluation: Much like the Examen in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, evaluation here challenges faculty to provide students with the opportunity to reflect on the process of action and what they have learned from their experience. In a well-structured evaluation exercise, students should then ask themselves what they did well and what they should do differently; but additionally, they need to evaluate WHY things worked or did not work as planned.

Teaching Practice:

Moving from the theory of Ignatian Pedagogy to teaching practice is something faculty may already be doing. Here are a few ideas to add to the lexicon of activities that may help students move into the meaningful learning practices that reflect Ignatian Pedagogy.

- Active Learning Strategies: have students stop and engage in the course material in a more meaningful and personal way. What examples can they find related to the content that are relevant to other classes, campus activities, current political situations, city or national news?

- Opinion Polls: periodically conduct anonymous polls to determine your students’ reactions to the materials. What is their understanding of the material or the concepts being taught? Are they able to apply what they are learning to another concept?

- Reflective Activities: Reflection does not have to come at the end of a course but can be used throughout to have students write about how they are interpreting what they are learning. What situation in their own life does this relate to? How is this content changing their views on how they view their surroundings? Their understanding of themselves?

- Student-Generated Content: have students bring in research, examples, ideas that relate to the course concepts. If a student brings something of particular relevance, share with the class and incorporate into the course materials. Having students bring in relevant content makes the course more their own and not just something dictated to them.

- Talk to students about why this subject matter is important in your discipline, to a general education or contributes to becoming a more informed person. What action have you taken as a scholar of your discipline? What actions do you continue to pursue to make you a person for others?

Works Cited

Arrupe, Pedro, S.J. “Men and Women for Others: Education for Social Justice and Social Action Today.” Address to the Tenth International Congress of Jesuit Alumni of Europe, Valencia, Spain. July 31, 1973.

Kolvenbach, Peter-Hans, S.J. As quoted in “Go Forth and Teach: The Characteristics of Jesuit Education.” Jesuit Secondary Education Association Foundations, 1986, pp. 18.

O’Malley, John W., S.J. “How the First Jesuits Became Involved in Education.” In The Jesuit Ratio Studiorum: 400th Anniversary Perspectives.” Vincent J. Duminuco, S.J., Editor. New York: Fordham University Press. 2000. Pp. 56-74.

Nicolas, Adolfo, S.J. “Depth, Universality, and Learned Ministry: Challenges to Jesuit Higher Education Today.” Remarks for “Networking Jesuit Higher Education: Shaping the Future for a Humane, Just, Sustainable Globe.” Mexico City, April 2010.

Society of Jesus. Ignatian Pedagogy: Practical Approach. 1993.