Loyola University of Chicago Herbarium

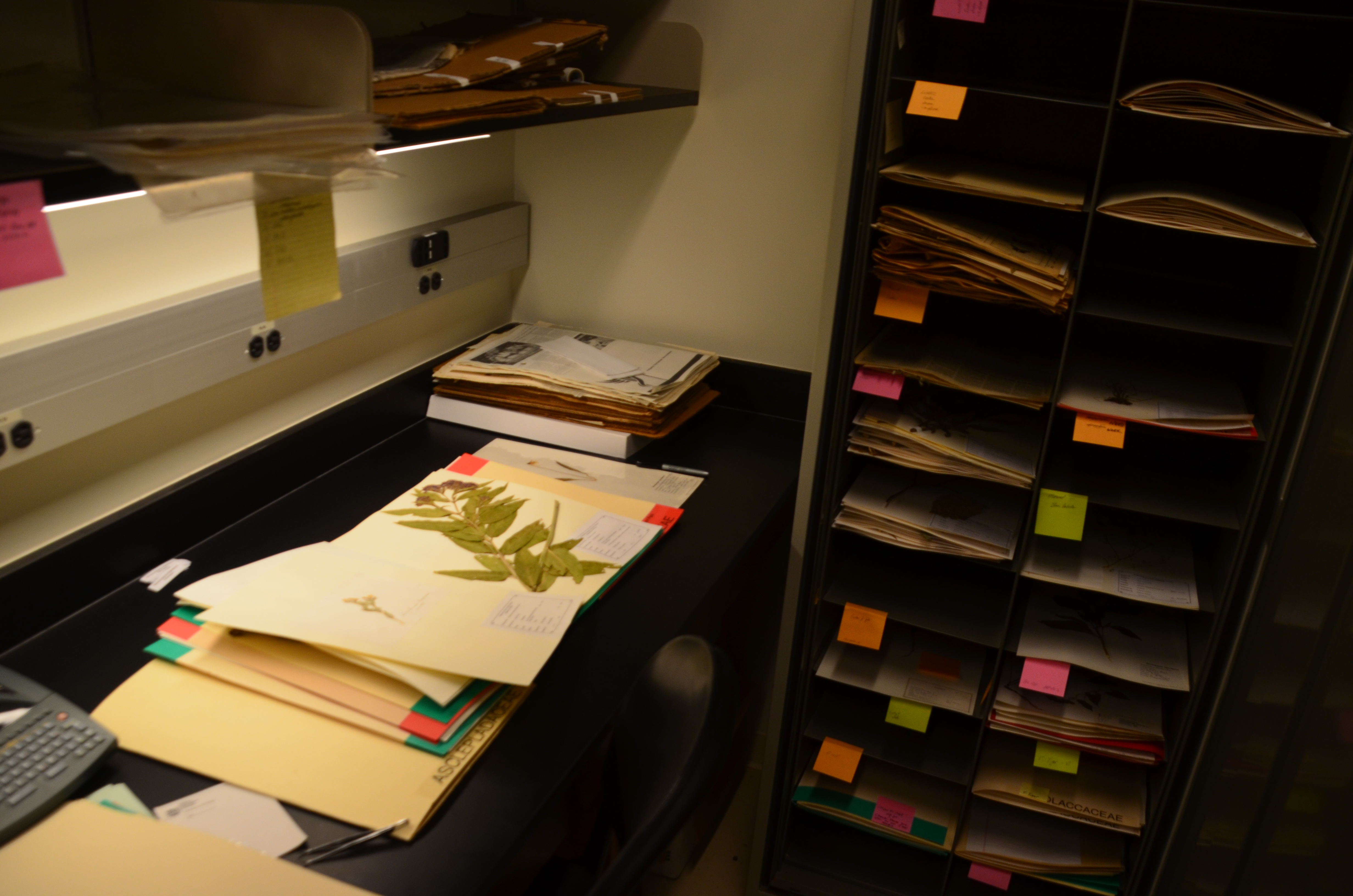

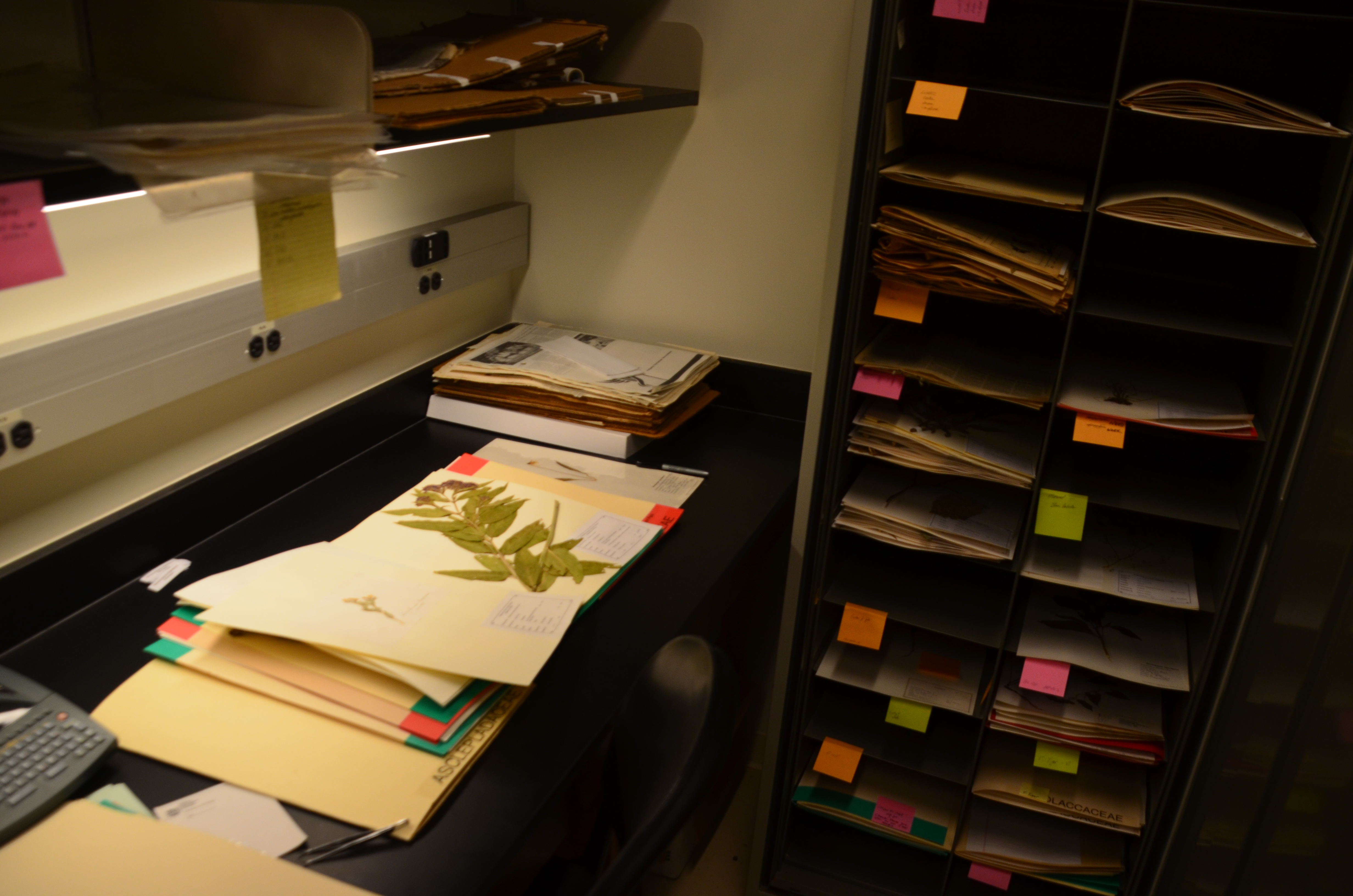

The plant collection of the Loyola University of Chicago Herbarium is housed in room 238 of the Quinlan Life Sciences Center. The workspace contains resources for plant identification as well as materials to press and dry them. Dried specimens are glued to herbarium paper, entered into a database, and filed.

Biology faculty, with the assistance of Loyola Library archivists, have uploaded the plant collection to the Midwest Herbarium Consortium's online system. This is one of ten regional North American portals integrated into the Symbiota-based portal network SEINet. Data in this network can be published to IDigBio and to GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility), which provides free, open access to biodiversity data. The herbarium is registered as LUC in Index Herbariorum, “a worldwide index of 3400 herbaria and associated staff where a total of 350 million botanical specimens are permanently housed” (sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/).

The Loyola collection of approximately 4000 specimens is small compared to the one million specimens databased at the Field Museum or the 600,000 at Notre Dame University. However, there is interest in small herbaria like Loyola’s because they often contain more extensive collections of certain species or of specimens from particular areas than larger collections might. Loyola’s collection has many specimens for example from the Cedar Creek Natural History Area in Minnesota, Jitterbug Lake in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, Glacial Park in McHenry County, and, of course, from the Loyola University Retreat and Ecology Campus (LUREC).

The purpose of herbarium collections was to identify and document plants collected from around the world and to maintain type specimens – that is the individual specimen upon which a species description is based. More recently herbarium collections have been put to much wider use: The occurrences documented may be used to map species’ migrations due to climate change; measure morphological changes over time and space; isolate DNA from dried specimens and relate to changes in distribution and structure; sample soil particles adhering to roots for the DNA of soil microorganisms; and maintain and share samples of plants used in research projects.

The next stage of this project will be to secure the equipment to allow us to digitize specimens so that images can be attached to online documentation.

Roberta Lammers-Campbell, Ph.D., Curator Emerita

The plant collection of the Loyola University of Chicago Herbarium is housed in room 238 of the Quinlan Life Sciences Center. The workspace contains resources for plant identification as well as materials to press and dry them. Dried specimens are glued to herbarium paper, entered into a database, and filed.

Biology faculty, with the assistance of Loyola Library archivists, have uploaded the plant collection to the Midwest Herbarium Consortium's online system. This is one of ten regional North American portals integrated into the Symbiota-based portal network SEINet. Data in this network can be published to IDigBio and to GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility), which provides free, open access to biodiversity data. The herbarium is registered as LUC in Index Herbariorum, “a worldwide index of 3400 herbaria and associated staff where a total of 350 million botanical specimens are permanently housed” (sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/).

The Loyola collection of approximately 4000 specimens is small compared to the one million specimens databased at the Field Museum or the 600,000 at Notre Dame University. However, there is interest in small herbaria like Loyola’s because they often contain more extensive collections of certain species or of specimens from particular areas than larger collections might. Loyola’s collection has many specimens for example from the Cedar Creek Natural History Area in Minnesota, Jitterbug Lake in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, Glacial Park in McHenry County, and, of course, from the Loyola University Retreat and Ecology Campus (LUREC).

The purpose of herbarium collections was to identify and document plants collected from around the world and to maintain type specimens – that is the individual specimen upon which a species description is based. More recently herbarium collections have been put to much wider use: The occurrences documented may be used to map species’ migrations due to climate change; measure morphological changes over time and space; isolate DNA from dried specimens and relate to changes in distribution and structure; sample soil particles adhering to roots for the DNA of soil microorganisms; and maintain and share samples of plants used in research projects.

The next stage of this project will be to secure the equipment to allow us to digitize specimens so that images can be attached to online documentation.

Roberta Lammers-Campbell, Ph.D., Curator Emerita